A water service consists of certain characteristics, such as quantity, quality, and continuity.

Published on: 11/03/2014

The distinction between the physical infrastructure (the pipes and pumps) and the service that this infrastructure delivers is fundamental. In many sectors, the concept of service refers to the provision of a public benefit through a continuous and permanent flow of activities and resources. A water service therefore consists of a flow of water with certain characteristics, such as quantity, quality, and continuity. We make the difference between the infrastructure and the service – which can be delivered through a variety of different management models. In the end it is the service that counts: what users get and what providers can supply.

The concept of 'sustainability' is used liberally in the sector. In the more specific context of the rural water sector, many organisations define sustainability as the maintenance of the perceived benefit of investment projects after the end of the active period of implementation. Hence, this definition may be closer to one that simply describes sustainability as: 'whether or not something continues to work overtime'; meaning, in this case, whether or not water continues to flow over time. A sustainable rural water service can thus be understood as the maintenance (or improvement) of a flow of water with certain characteristics over time.

There is often a disconnect between those who carry out the initial project cycle investment and those responsible for the long-term management of rural water services.

This conceptual understanding has a bearing on how we look at the life cycle of a service, and how this differs from hitherto common understanding of the life cycle of a water system. In the rural water sector, it is common to talk about a 'project cycle'. This usually refers to the capital-intensive period in which the physical infrastructure is typically developed and the management arrangements are put in place, such as the establishment of a water committee and the setting of a water tariff. After completing this project cycle, an undefined phase begins, involving long-term operation, administration and management; this is commonly referred to as 'O&M' (Operation and Maintenance). Even though this phase is much longer than the initial cycle – lasting for many years – and is crucial for sustainability, it usually receives far less attention. To complicate the picture further, in many country contexts there is often a disconnect between the organisations or institutions who carry out the initial project cycle investment and those that are responsible for the long-term management and support of rural water services.

In some contexts the concept of the 'life-span' of a water supply system is used, referring to the fact that any piece of physical infrastructure has a finite time after which it breaks down due to wear and tear or some type of natural disaster and will require replacement or upgrading. In more complex piped systems each major component (i.e. the intake, storage tanks, transmission lines, electro-mechanical pumps etc.) may well have different life-spans and require replacing at different times. The big question is what happens when a physical system – or major components – comes to the end of its lifespan and how to address this as part of the delivery of truly sustainable water services?

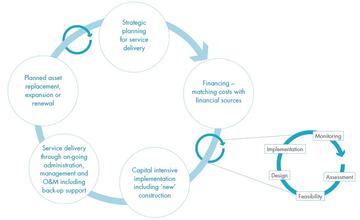

In order to address these challenges we conceptualise water services by a life cycle, consisting of various stages or phases over time (see figure below). A service normally starts with a capital-intensive period in which the physical systems are built, assets are developed and management arrangements are put in place as outlined above. Typically these consist of discrete implementation projects, with a series of consecutive activities including assessment, feasibility, design, implementation and project monitoring. This capital intensive period is followed by the phase of the service delivery itself, and consists of O&M and administration activities. During this phase, renewal of the non-physical elements of the service also takes place: water committee members may be replaced and retrained; tariffs may be reviewed; or, the bookkeeping system may be upgraded. When the physical system (or components of it) comes to the end of its lifespan, physical interventions to replace physical assets (above-ground structures, storage tanks, transmission pipes and pumps) take place. This is the so-called capital maintenance phase. Such activities happen in ongoing steps, but typically are carried out, again, through discrete projects, often at different moments in time for different components, as these have different lifespans.

Throughout the service life cycle there is an on-going need for planning for medium to long-term asset upgrade and replacement.

The cycle is closed when the service is expanded, for example, by extending to new, or initially un-served households, or by a major upgrade of the service such as moving from a borehole with handpump to a borehole with motorised pump and small distribution system. The service delivery life cycle, therefore, includes the 'new' investment stage, as well as the administration, O&M and eventual asset renewal and replacement and/or expansion stage in one continuous cycle.

It is important to underline that throughout the service life cycle there is an ongoing need for planning for medium to long-term asset upgrade and replacement and, very importantly, to identify the necessary financing sources to meet these ongoing costs. A clear and full understanding of all the costs required to deliver a reliable water service has been one of the major blind spots of the sector for decades. Policymakers, governments and development partners have rarely, if ever, known the full costs of services, including not only the initial construction costs, but also what it costs to maintain them in the short and long term, including eventual replacement and expansion costs, as well as costs for support to service providers.

Adopting and supporting a service life cycle requires thinking through all the costs of the service in each stage. This can then be used to have an informed debate about who should finance these costs. Both costs and sources of financing can be assigned to the different phases of the life cycle.

IRC advocates for the move from thinking in terms of project cycles to one of thinking in terms of service delivery cycles. We help our partners in making this shift, and particularly about those phases in the life cycle that have been under-resources: replacement, expansion and service enhancement. Moreover, IRC has been leading the development of the life-cycle costing approach, and leading that in India, Ghana, Burkina Faso and Mozambique under the WASHCost project. Since then, it has been applied in other focus countries like Honduras and Uganda.