This second blogpost of three on urban sanitation in Indonesia describes the mismatch between policy and practice. Politicians have set the ambitious target to make Indonesia open defecation free by 2019, but a recent visit to Indonesian municipalities makes me wonder whether striving for the end of open defecation will not prove to be a red herring

Published on: 03/09/2014

Urban sanitation has gained a presence on the national agenda in Indonesia, reflected both in the instalment of nationwide programs such as the Program Percepatan Pembangunan Sanitasi Permukiman (PPSP/ Road Map for Acceleration of Urban Sanitation Development) and a steady increased budget allocation at the central government level. Indonesia has also expressed the ambition to eliminate open defecation by 2019, with at least 85% of all sanitary facilities linked to a treatment system. This will be a daunting task if considered that Indonesia currently holds the inglorious second position in the list of countries with the absolute largest number of people practising open defecation with 54 million (WHO/UNICEF, 2014). While typically a rural issue, in Indonesia the percentage of urban dwellers practicing open defecation is estimated at 14%, almost 18 million people (WHO/UNICEF, 2014). It would seem that this ambition by the national government is proof that international attention and naming and shaming techniques work. Currently, the budget to reach this ambition has been calculated and is awaiting approval of the new president and parliament. Despite all this much needed focus on sanitation, my recent visit to Indonesia made me wonder whether this ambitious target will be reached in such a short time and whether it is the most relevant issue to tackle.

The power of numbers

During my recent visit to Indonesia, attending various meetings at municipal and provincial level with staff of the USDP (see blogpost 1 for a description of the program), I encountered this target of eliminating open defecation by 2019 over and over again. This objective, despite yet being formally adapted as a national policy, featured in the draft citywide sanitation strategies (SSK) of various municipalities that were presented at a meeting I attended at the Aceh Province Planning Department. However, it was just a number. No plans on how to achieve it: no massive behaviour change campaigns, just the construction of some public toilets and septic tanks. The accompanying USDP staff disclosed to me that most municipalities had already copied this target it their plans even though it was not a formal national policy yet; however, this was done without really thinking it through. When I discussed this issued during my debriefing presentation back atthe Environmental Health Directorate in Jakarta, it came to me that this was a public secret at the ministry. As all the staff members present at the debriefing session looked at each other, it was evident that all knew that this target of eliminating open defecation by 2019 is not realistic, for it will never be reached in time. However, as is often the case within bureaucratic hierarchies, there is a difference between knowing and being 'instructed' through a ministerial decree.

This episode made me wonder what it is that we are actually attempting to achieve as a water sanitation and hygiene (WASH) sector. International campaigns and targets such as the Millennium Development Goals are well intended, but one can wonder whether they are worth the effort if they only lead to empty commitments by national governments at the headquarters of the United Nations or the World Bank. Clearly, governments which make commitments under pressure of external actors are not accountable to their own citizens to meet these; neither is it likely that these international agreements will lead to any form of political commitment at the local level such as in a municipality. In fact, these types of unrealistic targets mainly result in pressure felt by public offices to 'fudge' the numbers here and there in order for a government to meet set goals (see the article by Hueso and Bell below on how this 'fudging' has led to a total failure of India's Total Sanitation Campaign).

The neglected issue of faecal sludge

A second issue that has increasingly received attention within the WASH community is the importance of faecal sludge management. For a long time, especially when considering rural sanitation, sanitary problems have been equated to open defecation problems. The solution has been to build a pit latrine and use this for safe containment of faeces. For scarcely populated areas this problem will certainly match the solution (provided that the latrine isn't constructed too close to a water well). This has led many international WASH programs to focus on latrine construction as the solution to sanitation problems; 'when one pit is full, one can always construct a new one', has been the dominant sector thinking for a long time. In urban areas, however, sanitation problems do not only equate to safe containment of faecal matter, but also to its safe collection, transportation, treatment and safe disposal or reuse, for instance as fertiliser. High population densities make it impossible to construct ever more latrines and open drains filled with raw wastewater cause environmental and health risks to an entire city.

Many people in Indonesian cities have a toilet connected to a septic tank. However, in many cases these so-called septic tanks are bottomless; making them more leakage pits which rely on the absorption of the faecal matter in the subsoil. The vast majority of the septic tanks, with and without a bottom, are attached to a pipe which disposes of the effluent in open drains or creeks. The few people that actually have their septic tanks emptied pay the driver that collects the septage, and cannot be sure whether this is subsequently delivered to a faraway treatment plant, illegally dumped in a nearby creek or directly sold to a farmer without any treatment.

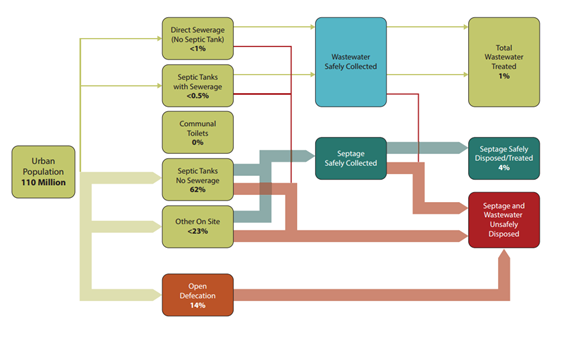

Figure 1: Wastewater and septage flows in urban Indonesia (source:(The World Bank & AusAid, 2013, p. 6)

From the figure above it becomes clear that the vast majority of faecal matter entering the open environment generated in cities, does not come from open defecation. Untreated human waste in urban areas forms 95% percent of total generated volumes, but of this only 14% originates from open defecation. The remaining 81% is all the septage which finds its way to open drains, streams and into the groundwater. This makes it beyond doubt the most pressing issue regarding urban sanitation in Indonesia. Clearly it will remain imperative to build toilets and septic tanks (individual or communal) for the remaining 14% in order to meet the requirements for these people to live a dignified life. But merely focussing on eliminating open defecation without tackling the issue of faecal sludge will only shift the sanitary problems, not solve them.

The way forward

However, there are also some innovative ideas being developed on faecal sludge management which I've taken back from Indonesia. One management model developed and tested by the USAID-financed IUWASH program seems very promising. Their idea has been to move away from the current system when one calls a faecal sludge emptying service when the tank is full, to one where a service is provided every three years for the entire neighbourhood. Residents then pay a small monthly surplus on their water fees or municipal tax instead of a high one-off tariff. As residents pay the service provider, and not the driver there is a higher incentive of the driver to limit illegal dumping. Moreover, as whole neighbourhoods are tackled at once, smaller trucks can empty tanks inside narrow lanes and then deliver to larger trucks, which bring the sludge to the treatment facility, thereby reducing the number of long trips to this facility. New septic tanks can even be constructed by the service provider with construction costs being spread out throughout the service contract lifetime. Initial testing of this new model seems promising and forthcoming research carried out by WSP points out that residents seem interested in this payment model.

Despite its promising aspects, this model will still face some hurdles before it can be implemented across Indonesia's 506 Cities and Districts. Technically, there will certainly be some challenges to find an optimal emptying frequency of septic tanks, keeping in mind that the tanks which are already installed differ in dimensions. Furthermore, it will require some efforts to convince system owners to pump out their tanks, even if they haven't had any problems with their systems so far. At a managerial level it will certainly be a challenge to find an appropriate service provider that can carry out this work, invest in a fleet of trucks and collect fees. Some experiments have been carried out to combine this with the water utility or with the electricity company. But most of all, the biggest challenge of the future will be to nurture the political commitment throughout these 506 local government bodies, so that they may be willing to implement this model; in other words, marrying the scale of PPSP with the innovations of IUWASH. The last blogpost of this series will discuss more in depth on how to build local political commitment while continuing to strive for change at scale.

At IRC we have strong opinions and we value honest and frank discussion, so you won't be surprised to hear that not all the opinions on this site represent our official policy.